Bushes denuded of foliage by Podacanthus wilkinsoni.

| Page 1 |

From AGRICULTURAL GAZETTE OF N. S. WALES.

16: 515-520

June, 1905.

Miscellaneous Publication, No. 862.

WALTER W. FROGGATT, F.L.S.,

Government Entomologist.

THE large size and grotesque form of the orthopterous insects belonging to the Family Phasmidæ, better known under the popular name of Stick or Leaf insects, has always brought them under the observation of entomological collectors, and though very little is known about the early stages of the development of our commonest species, many of our larger ones were described at a very early date, chiefly by G. R. Grey, Westwood, and Macleay. Isolated descriptions of single specimens are apt to be misleading, as the difference in the sexes in some species is so marked that it has led to them being frequently described as distinct forms. In some groups both sexes are wingless, in others while the females are wingless the males are furnished with large flying wings, and are much smaller and slender in form.

They are amongst the most helpless of insects, and from their large size are destroyed by many birds, but, in compensation for their helplessness, nature has endowed them with most remarkable powers of imitative mimicry to the foliage among which they live and feed. Not only do their colours harmonise, but their wings, legs, and head are often covered with leaf-like spots and markings, the margins scalloped and crenulated in imitation of their food plants, so that in spite of its large size, if the insect remains motionless, it will easily escape detection right under one's eyes. They have a general appearance to the carnivorous Mantis, which, however, puts on its mimic livery to more easily capture its prey, but they can be distinguished at a glance by the difference in the structure of the fore legs which are used for walking, and are without claws or spines. They lay their eggs singly, dropping them on to the ground below, while crawling among the foliage. The eggs are rounded, enclosed in a very hard shell, and many of them are wonderfully like seeds. They often remain for upwards of two years on the ground before the larva makes its way out, a helpless stick-like creature, with slender body and legs, and though no parasitic enemy could get at them in the egg state, such helpless creatures as these baby phasmids must have an immense number of enemies in the first few weeks of their childhood. Australia is rich in large and remarkable looking species of phasmidæ, about fifty-four having been described, while probably in the interior many others

| Page 2 |

The Ringbarker (Podacanthus wilkinsoni, Macl.).

This stick insect was described by Macleay in the Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales in 1889, from specimens obtained by the late Government Geologist, Mr. C. S. Wilkinson, near Binda Caves, who stated that they were so numerous at that date that large tracts of forest trees were completely stripped of their foliage, and appeared to be dying from their attacks. Macleay in commenting upon these notes said that it was probable that in many cases where the trees were found to be dying out, from no apparent cause, that it might frequently be brought about by the infestation of this or other allied species of plant-eating phasmids.

Bushes denuded of foliage by Podacanthus wilkinsoni. |

Through the kindness of Mr. J. F. Campbell, the District Surveyor at Walcha, with whom I have been in communication for a few years on this interesting subject, I was enabled this season, 1905, to visit the district infested by this gregarious stick insect, collect specimens, and make notes on the damage caused by their presence.

The country over which they range is about 50 miles long, comprising a wide strip of forest, including what is known as Murphy's Scrub, through Upper Tia, and Noundoc Station to the Gulf, a depression in the mountains towards the Manning River, in which district they are known as the “Ringbarkers,” “Murphy's Ringbarkers,” or “Lowrie's Flying Gang,” on account of the dying brown appearance of the trees covering the ranges after they have been feeding through them. So like the effects of ring-barking upon the trees is this damage, that I was told that many years ago the forester, new to

| Page 3 |

All species of eucalypts are devoured, but no other scrub trees are molested.

The young insects emerge from the eggs upon the ground in the early summer, but are not noticeable until they take on a yellow and black banded tint; growing rapidly, the bulk of them are full-grown about New Year, and commence laying their eggs towards the middle of February, and continue into March, when those that survive die with the first frosts which may come early in April in this district. Therefore, the eggs now being laid will remain dormant until the early summer of 1906, and the next crop of phasmids will be at New Year, 1907.

The adult male measures 3½ inches from the front of the head to the tip of the abdomen, with the slender antennæ in front about an inch longer, and across the expanded wings 4 inches. The general colour is dull green with brownish tints on the legs, the tegmina or forewings leaf-like, and edged with white on the outer edge, the hind wings with the front stripe opaque green, the base orange red, all the semitransparent portion pink with a shade of purple.

The head is rounded, the mesothorax forming a rounded neck covered on the upper surface with a number of conical spines; the legs and abdomen long and slender, the latter furnished with a clasping apparatus above the genitalia, and slender cerci at the extreme tip of the abdomen.

In several immature males collected at the same time, the mesothorax is fully twice the length of the adult, without any dorsal spines; the tegmina and wings small and rounded at the tips; the thighs of the hind leg stout and cylindrical, with two large black spines in the centre of the under surface not present in the perfect insect, and the male genitalia and claspers are undeveloped, simply represented by a swelling at the apex of the abdomen.

The female is of a very similar structure in the head, legs, and thorax, but of a lighter green tint, though it is very variable. The tegmina is light green, with the front margin of the hind wings of a similar tint, except the basal portion, which is a rich reddish orange tint, the membranous portion a deep purplish pink, somewhat brighter than that in the male wings. The abdomen is swollen, but tapering to the tip, is of the same green tint as the tegmina, with pinkish markings between the wings; the under surface of the abdomen roughened and almost black. On account of her thickened abdomen she looks shorter than the slender male, but the measurements both in length and across the wings are about the same. There is a variety often noticed among the females which have the whole of the tegmina, front of the wings, and abdomen reddish salmon colour.

The eggs are over one-sixth of an inch long, rounded behind, truncate at the summit, with a round plug projecting from the centre like the stopper of

| Page 4 |

Extatosoma tiaratum. |

The forest country, tenanted by this phasmid army at present, contains little timber of special value, but though they have been confined to this strip of country for so many years without spreading to other districts, altered conditions might cause them at any time to spread.

The clearing of tracts of country in their haunts has now broken up the once united swarm into several minor armies, and when once they can rise from the ground they can fly very well, and their wings (before the females become distended with eggs) are capable of carrying them considerable distances with a favourable wind. In good forest country they would cause immense damage, for the trees, denuded of their foliage, shoot out from the butts, often forming quite a thick scrub, and the wood does not split freely where it is being constantly damaged. In such a way the phasmid could develop into one of the worst forest pests in Australia, and be one very difficult to deal with.

| Page 5 |

The Spiny Leaf Insect (Extatosoma tiaratum, Macleay, W. S.)

This species was originally described by W. S. Macleay in the appendix of King's Survey, published in 1827, under the name of Phasma tiaratum, but as the insects collected during King's voyages came from all parts of the Australian coast, there was no exact locality given. In 1833 G. R. Grey, published “The Entomology of Australia, Part I; Monograph of the Genus Phasmidæ,” illustrated with fine coloured plates of all the then known species; in it he figured and described both sexes of this insect, calling the male “Hope's dilated-bodied Spectre,” a rather cumbersome name (Extatosoma hopei), though he seems to have thought it might be the male of Macleay's

Extatosoma tiaratum on Japanese Holly, showing imitative mimicry. |

The female measures up to 5 inches in length from the front of the head to the tip of the abdomen; general colour dark green with the upper surface clouded with a smutty tint, like that upon the foliage caused by black fumagine, while the sides of the segments are mottled with

| Page 6 |

[One Plate.]

Stick Insects

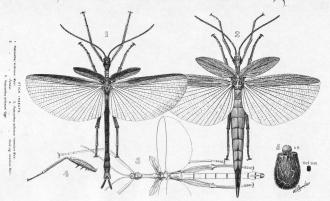

1. Podacanthus wilkinsoni (male),

2. Podacanthus wilkinsoni (female),

3. Podacanthus wilkinsoni (immature male),

4. Podacanthus wilkinsoni (hind leg, immature male),

5. Podacanthus wilkinsoni (egg).

Sydney: William Applegate Gullick, Government Printer. - 1905.